Because I Said So

There’s something compelling about a book collection that has a focus and a set of rules entirely of your own making, one that includes titles you alone deem important and is complete only when you say so. Sometimes collections like this are regarded to be of sufficient importance that research libraries come calling, with requests to mount exhibitions or to acquire the materials for their own scholarly purposes.

The outstanding example of this phenomenon, in my view, is the George Arents Collection on Tobacco, thousands of objects in 20 languages—broadsides, cigarette labels, advertising ephemera, literary manuscripts, trading cards, books too, of course—all related in one way or another to the history and lore of the “evil weed.” Gathered in the early years of the 20th century by a former executive of the American Tobacco Company—George Arents didn’t think smoking was evil at all—it is now a choice holding of the New York Public Library, with a room and a staff of its very own on the third floor.

Board had a volume printed on dried pasta held together by steel bolts.

A collection I particularly admire—I wrote about it in A Gentle Madness—was the brainchild of the late Fred J. Board of Stamford, Conn. A resourceful man who collected miniature books and guides published by the WPA’s Federal Writers Project, Board also collected a bibliographical mélange under the general rubric of “oddities.” To be fair, the idea was not of Board’s own invention—the endeavor was inspired by Bookman’s Bedlam, a 1955 book written by Walter Hart Blumenthal. Board bought Blumenthal’s collection en bloc and then augmented with his own additions. Still, he took it to such bold new heights that the concept pretty much became his alone.

Among Board’s treasures was a book shaped like the state of Georgia, an atlas 5' 9" long, tomes salvaged from sunken ships, books bound in skin (human and otherwise), a volume printed on purple paper. He had a volume printed on dried pasta held together by steel bolts, and another still that opened like an accordion. Board owned several hundred of these oddities, all of which had something to say not only about the people who conceived them, but about the person who saw merit in assuring their preservation. “The beauty about my collection is that it’s endless,” Board told me. “There’s no bibliography, there are hundreds of curious things in the world, and I’m the one who decides what is strange and unusual.”

I guess what I like most about this kind of dynamic is its subjectivity, a quality I sensed immediately in a recent exhibition at the Boston Public Library, “Covering Photography: Imitation, Influence and Coincidence,” a show of books collected by professional photographer Karl Baden, an art instructor at Boston College. The books shown in 17 display cases at the public library represent only a fraction of the 2,500 Baden has collected over the past 30 years; and you might say they’re merely a sideline to his main collection. (Baden wrote about his principal pursuit, the history of photography, in a “How I Got Started” piece for the January/February 2007 issue of FB&C.) But as kindred spirits to the collections of George Arents and Fred Board, they’re of uncommon interest to me.

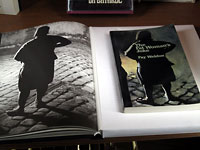

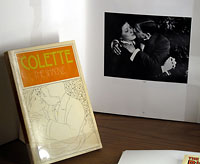

The object of Baden’s passion in this case is not the books’ content, but the distinctive jackets that adorn them. “The books,” Baden explains in the online introduction to the exhibition, “are not here because of their content; they are here because of their covers: storyline, subject matter—everything that takes place between the covers is, for the purposes of this show, secondary, if not incidental.” The Boston exhibition—which will travel later this year to Syracuse University, where Baden, 56, earned an undergraduate degree in 1974—included 57 books with jacket art that either used outright, or through what he calls imitation, influence or coincidence, representations of photographs by such masters as Man Ray, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. (For those interested in knowing more about the complete collection, Baden has a website that is fully searchable by photographer, author, publisher, publication date, and designer; he also posts, on a regular basis, “covers of the month,” one of the more recent installments, photos from the Depression.

“Because of my profession, I am interested in the history of photography, and I have collected that rather thoroughly,” Baden told me in a recent interview. “I began the other collection as a derivative pursuit, mainly because I really enjoy the thrill of the hunt. One of my rules of collecting is that I do not buy these books on the Internet. I know that if I want a certain book, I can find it online, but for me, as a collector, it’s about thinking actively, it’s about looking for something that gets passed up. This sideline collection allows me to do that, because I have to know it when I see it. When you pick one of these books up out of the pile, you realize that it has some sort of value. That’s what I enjoy. I never pay more than a couple dollars for any of these, and I have paid as little as ten cents.”

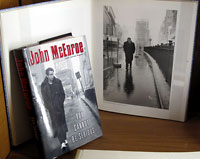

The way the process works is fairly straightforward, Baden continued. “I’ll look at a book, and say, ‘That looks like an Ansel Adams photograph.’ Sometimes the covers are very similar to famous photographs, and sometimes they are an actual re-doing of a photograph in another medium, a restaging. To cite one example: there is a very famous photograph taken in Times Square by Dennis Stock for Magnum that clearly inspired the cover art for the hardcover edition of John McEnroe’s autobiography, You Cannot Be Serious. There’s no doubt it’s meant to reference that photograph—so you ask yourself, why? To make this kind of collection work, needless to say, have to know the original photographs. That’s where I get my edge.”

Nicholas A. Basbanes recently received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to work on his book on paper, which is forthcoming from Knopf. His most recent book is Editions & Impressions, a collection of essays. His other works include the acclaimed A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.

Nicholas A. Basbanes recently received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to work on his book on paper, which is forthcoming from Knopf. His most recent book is Editions & Impressions, a collection of essays. His other works include the acclaimed A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.