In the Trenches

British surveyors made a crucial contribution during World War I—an accurate map of the battlefield By Jeffrey S. Murray Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada. He recently published Terra Nostra: The Stories Behind Canada’s Maps, 1550-1950 (Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006).

When the British army—or more accurately the British Expeditionary Force (BEF)—first embarked for war against Germany in August 1914, its leaders were expecting a war of movement. Looking back on their Boer War experience from twelve years earlier, artillery commanders thought they would be fighting in the open where they could observe their shell bursts and adjust their fire accordingly. But with the opening battles of Flanders and the complete entrenchment of both armies along a Front stretching from the Swiss border to the North Sea, British gunners were now desperate for help directing their fire onto German targets. Nothing less than an accurate, large-scale map of the battlefield was needed.

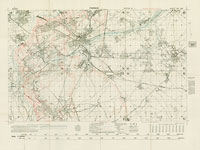

Some large-scale maps of northeastern France already existed, but their quality was inconsistent, they were often out of date, and they covered only a small portion of the theatre of operations. By November 1914 it had become obvious that a completely new topographic map would have to be made, one that would include a re-survey of some 12,000 square miles of the French countryside. It would be a formidable undertaking because much of the region either lay in German hands or within range of their guns. Although work on the new map began almost immediately, and large-scale maps would be ready for the British spring offensive, it was well into 1916 before a complete system of maps would be ready for the entire Western Front. The new British map was printed at three different scales: 1:10,000, 1:20,000, and 1:40,000. For the most part, all three maps showed the same basic information, being drafted first at 1:20,000 (roughly 3 inches to a mile), then either enlarged or reduced to one of the other two scales. Intelligence information on the German lines was added to all three scales as overprints, a move which enabled mapmakers to update their intelligence to reflect the quickly changing situation on the battlefield without going to the trouble of reproducing the entire topographic base map each time.

The 1:20,000 scale was the most popular topographic map. Given the reference number GSGS 2742, it was considered the best scale for mapping trenches and for showing special ‘target’ and ‘position’ information on German railways, supply dumps, machine-gun and mortar emplacements, wire entanglements, and observation/listening posts. For this reason, the map was preferred by medium and heavy artillery, and for counter-battery work. It was also a favorite among airmen who used the detailed trench outlines to fix target positions in an otherwise featureless muddy terrain. The larger 1:10,000 map (GSGS 3062), on the other hand, was primarily intended as an infantry trench map, and the smaller 1:40,000 map (GSGS 2743) was used mostly in planning.

To meet artillery needs, the 1:20,000 maps were usually cut into squares and pasted to artillery boards. Originally a French idea, the artillery boards had a zinc coating that minimized distortions caused by fluctuations in humidity and permitted a more accurate measurement of a target’s bearing and range. By mid 1915, British gunners were using the boards to shoot straight off the map without any preliminary registration—or practice shots. ‘Map shooting’ allowed British gunners to conceal their weapons from German observers until the opening salvoes of a campaign. Catching the Germans off guard gave the BEF an enormous tactical advantage and was called “one of the wonders of the war” by Maj.-Gen. Franks of the Royal Artillery.

Further Reading

The definitive history on British military cartography on the Western Front is Peter Chasseaud’s monumental Artillery’s Astrologers: A History of British Survey and Mapping on the Western Front, 1914-1918 (Lewes [England], Mapbooks, 1999). For a more condensed treatment of the maps produced by the BEF, see Peter Chasseaud’s Trench Maps: A Collectors’ Guide Volume 1: British Regular Series 1:10,000 Trench Maps GSGS 3062 (Lewes [England], Mapbooks, 1986), and “British Artillery and Trench Maps on the Western Front 1914-1918.” The Map Collector, no. 51 (1990), pp. 24-32.

Despite the surveyors’ best intentions, many of the old-school gunners thought these new techniques were an ungentlemanly way to conduct war. “A lot of the old traditional gunners, when they found … that people were trying to develop accuracy in shooting were appalled,” wrote Canada’s Lt.-Col. Andrew McNaughton while planning for the 1917 assault on Vimy Ridge. As one artillery officer once put it, “you surveyors with your angles, co-ordinates and logarithms—you take all the fun out of war.” They figured artillery units were supposed to fire at the opposing infantry, not at each other.

As the BEF’s mapmaking improved, demands for a broader range of maps began to be heard from the Front. Soon the BEF found itself producing daily situation maps showing the positions reached by their infantry during a major assault. Usually the information was overprinted onto existing 1:10,000 or 1:20,000 topographic maps. Transportation and communication maps at scales of 1:40,000 or smaller were also in high demand. They offered information on methods of communication between front and rear areas, and included notes on traffic directions, water supply schemes (vital for horse-drawn transport), telephone cable routes, railway lines, and tram routes. Also a favorite were the message maps compiled from small sections of the regular 1:10,000-scale map. The form on the reverse side made them very useful for communicating with headquarters during the course of a battle.