Wishful Thinking

Europe’s search for a quick route to the Orient led to some rather unusual ideas about the North American landscape By Jeffrey S. Murray Jeffrey S. Murray is a senior archivist at Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa, where he has helped to acquire nationally significant records on Canada’s cartographic heritage for more than twenty-five years. He recently published Terra Nostra, 1550-1950: The Stories behind Canada’s Maps (2006).

Throughout Europe’s great Age of Reason, no one wanted to doubt the existence of a navigable, all-water route through the North American continent to the Orient. For financial brokers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the spices and silks of Cathay promised far more lucrative returns than anything the New World had to offer, including its fledgling fur trade. Explorers found they could easily convince their European backers that if they financed just one more expedition into terra incognita, a route to Asia might be found. Some modern-day scholars question whether the explorers really believed such a route was possible. One thing is certain, however. Without the lucrative returns promised by a Northwest Passage, monetary support for explorations in the great northwest would not have been as readily forthcoming.

No wonder early Spanish, Russian, Dutch, French, and English explorers made the most of any natural feature that offered the slightest hint of a way around or through the continent. Since so little of the land mass was known, the region became a fertile ground for some highly speculative cartography. As early as 1601, for example, the great French explorer and statesman Samuel de Champlain was promising his benefactors in France that the St. Lawrence River was their ticket to an empire of riches. “By this [route],” he optimistically predicted, “we will be able to go to Cathay … We will be able to make the voyage in one month or six weeks without any difficulty.”

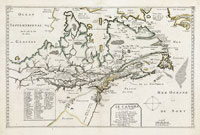

Although many European cartographers avoided the question of a passage, others were more than willing to facilitate and enrich the debate. They speculated on the nature of the passage and its extent, and covered much of the northwest with waterways that, in hindsight, now appear extremely naïve. There were essentially two competing theories as to what form an all-water route might take.

One saw the passage as a great river system that either extended west from the Great Lakes or east from some unknown bay along the west coast. La Grande Rivière de l’Ouest, as the French called it, had its beginnings in 1720s when the Sieur de La Verendrye took command of the Postes du Nord—the French settlements at Kaministikwia, Nipigon, and Michipicoten. His interest focused on the string of lakes and rivers west of Lake Superior, which we now know as the Lake of the Woods system. Natives from this area told him of a river which flowed straight west to a great inland lake called Lac Ouinipique (Stinking Water). Another river was said to continue from the outlet to this lake for some ten days and then discharge into a large ocean. La Verendrye concluded that this ocean was the Pacific, and that the final discharge would be somewhere north of California.