Comic Cartography

The witty world of cartoon maps

By Jeffrey S. MurrayJeffrey Murray is a former senior archivist with Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, Canada. He is the author of Terra Nostra: The Stories Behind Canada’s Maps, 1550-1950 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2006).

Most editorial cartoonists will probably tell you that they get as much hate mail as they get letters of commendation. While some cartoonists may have had their work recognized with international awards, others have been taken to court, their homes fire-bombed, and their lives threatened by religious fundamentalists. Yet, despite all the attention, the greatest satisfaction for most cartoonists comes from knowing they are providing an alternative voice to the conventional views of day-to-day events—views that have been handed down to us by politicians and business leaders. As cleverly crafted jokes, political cartoons allow dissention, but in a socially recognized forum. They are a platform “to yell back at the machine,” as Canadian cartoonist Duncan Macpherson once penned. They stand as a record of our scepticism to the views of mainstream media, and may be the only true history of our times.

Political cartooning can be traced back to sixteenth-century Italy and earlier. In the English-speaking world, it did not come into full bloom until the late eighteenth century when the satirical drawings of British printmaker and seller James Gillray (1756-1815) hit the streets of London. On this side of the Atlantic, it was the political cartoons of the Scottish-born book illustrator and satirist William Charles (1776-1820) that first popularized the genre with American audiences.

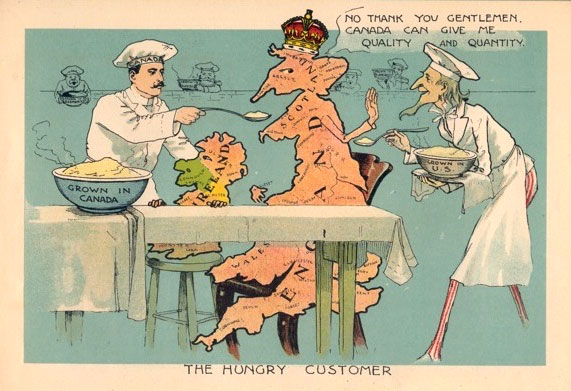

Since the days of Gillray and Charles, cartoonists have been using crude representations of maps and globes to provide an instantly recognizable place or to identify a region that is the target of their biting wit. Cecil Rhodes standing astride a map of the African continent with a telegraph line in his hands is a cleverly crafted statement on British imperialistic ambitions towards the “dark continent” which operates on several levels. For those who considered the continent “theirs” for the taking, the cartoon is a source of pride for the “might of the right;” for those who lie under Rhodes’ boot, the cartoon is a summation of their worst fears.

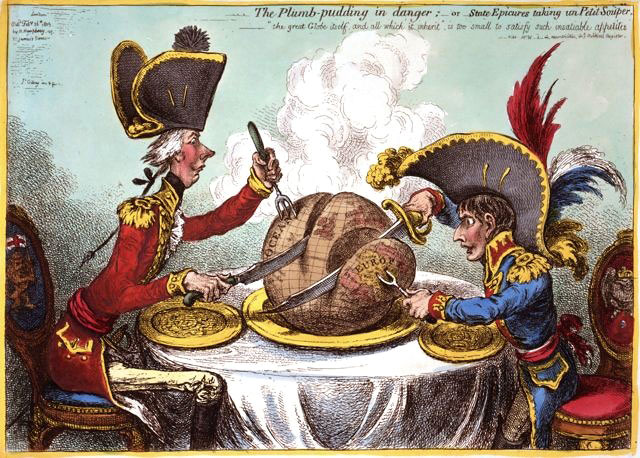

Maps and globes also offer cartoonists with easily recognizable objects that their caricatures can contort and manipulate for the sake of social commentary. Gillray’s famous print of William Pitt and Napoleon eagerly sharing the world as if it were a plum pudding must have been highly controversial when it appeared in 1805. Gillray’s alternative view of world affairs has Napoleon carving off Europe while Pitt takes most of the oceans. The cartoon was published after Napoleon’s victory at Austerlitz gave France military dominance in Europe, while Britain's victory at Trafalgar established its naval supremacy. In Gillray’s words, their great hunger for world dominance left “the great Globe itself … too small to satisfy … insatiable appetites.”

Cartoon humor is a great equalizer; it levels the playing field so that everyone is treated the same no matter their ethnicity, class, or gender. The humor exposes the prejudices, fears, and hopes of their times. But to employ this humor effectively, ventures Terry Mosher (a.k.a. Aislin) in The Hecklers, cartoonists must be “street-wise” and “must have experienced the frustrations of the average citizen with the suspicious factors that exert control over our lives. This experience hones the pen far better than a degree in political science.” President Jimmy Carter’s attempt to heal the world’s problems with his magic touch is a contrary view to America’s new US foreign policy announced in May 1977. The creator, Duncan Macpherson, seems to have as much faith in the government’s ability “to get it right,” as he has in an evangelical country preacher.