Collecting the Revolution

My collection, meanwhile, has grown from a few books to a few hundred—ignoring the advice to specialize. If a collector has that kind of discipline and focus, that is great advice indeed. I’m still at the kid-in-a-candy-store stage. I buy a first edition of The Journals of Each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775 for $280 one minute—and in the next plunk down a buck for a biography of John Paul Jones, a founder of the Navy.

“A collection doesn’t have to be filled with rare books, just good books,” Ken Gloss said to me. He owns The Brattle Book Shop in Boston. On my last road trip there, I filled up my trunk with good books, coming home with a beautiful fourteen-volume set of The Writings of George Washington published in 1889 by G. P. Putnam’s Sons ($500) and a biography on the complex Life of Joseph Brant-Thayendanegea Including the Indian Wars of the American Revolution. (Brant was a Mohawk leader who fought for the British and was falsely accused by America of committing atrocities during the war.)

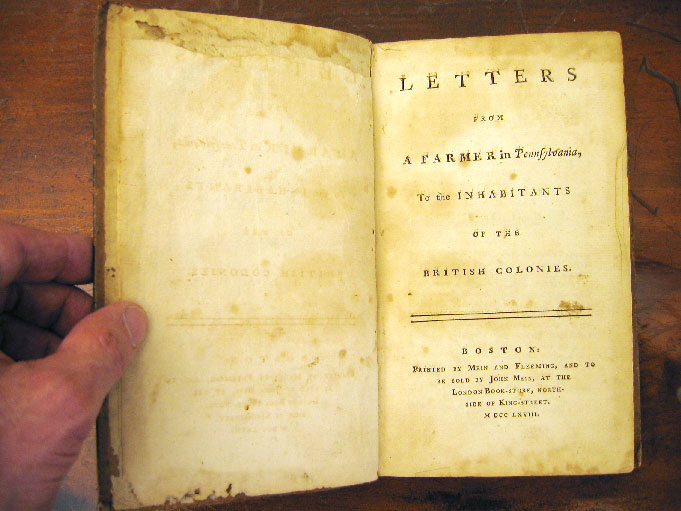

If I didn’t work for a nonprofit organization, I might return to Brattle with an attaché case and pick up one of his copies of the Declaration of Independence. My higher-tax-bracket fantasy would also involve a stop in New York on the way home. I’d head to Bauman for a first printing of the 1765 Stamp Act ($24,000) in a custom clamshell box and an early edition of Common Sense or a letter signed by John Adams. Then I’d get back on the interstate and stop at MacManus for a copy of John Dickinson’s Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer printed by Mein and Fleming in 1768 ($5,000).

In reality, the Revolution as a collecting area is so big, great finds turn up everywhere—bookshops, marquee auctions, online auctions, antiquarian book fairs, yard sales, estate sales, library friends groups’ sales, and thrift stores. Don’t forget flea markets. I still weep with jealousy every time I think about the Philadelphia man who discovered a first printing of the Declaration of Independence inside a frame he bought at a flea market in Adamstown, Pennsylvania.

Manuscripts might not always be readily available—or in your budget when they are—but one area that’s ripe for picking is newspapers.

“Newspapers are much more affordable today,” Wolf said, bringing joy to this former reporter’s heart. “There are so many more of them onto the market because they’re being digitalized and released.”

Salt Lake City-based bookseller Ken Sanders encourages people learn as much as they can about the Revolution—whether through newspapers, rare books, or anything else. The demand at his shop is strong, too.

“The history of our founding belongs to all Americans,” said Sanders, who remembers people pouring out of the Wasatch Mountains and standing in line for blocks when a tour of the Declaration of Independence came to town. “You could explore an area of the Revolution that hasn’t been heavily mined or you could take an area in a new direction.”

Gordon Gibson of Gibson Galleries in West Caldwell, New Jersey, has helped me broaden my perspective by illuminating more of the British point of view of the colonists’ quest for independence. I bought a pair of one of my all-time favorite series of books there: The Annual Register, Or A View Of The History, Politics and Literature. Fascinating on so many levels (where else could I read about authorities finding a dead man stuck face down in a well after apparently trying to save his dog?), the series provides a year’s worth of detailed news in what then passed for a timely manner.

The writers reviewing the year 1777 ($375 with a modern marbled cover) make it clear that England blundered by hiring Hessian mercenaries to kill Americans—a subject I read nothing about in school.