Not Wisely

In London, a Wealthy Iranian-American Collector Loved Too Well

By Jeremy B. Dibbell

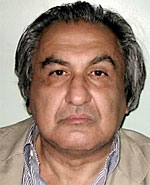

“You have a deep love of books, perhaps so deep that it goes to excess.” With these words, British judge Peter Ader passed sentence last month on Farhad Hakimzadeh, 60, a Harvard- and MIT-educated American citizen of Iranian descent. The London resident admitted to the mutilation and theft of rare books at the British Library and Oxford’s Bodleian Library.

Hakimzadeh, the former head of the Iranian Heritage Foundation, is a multi-millionaire businessman and published author, whose most recent work, co-written with Willem Floor, is The Hispano-Portuguese Empire and its Contacts with Safavid Persia, the Kingdom of Hormuz and Yarubid Oman from 1489 to 1720: A Bibliography of Printed Publications, 1508-2007 (2007). He currently directs a publishing firm, and is also a voracious collector of rare books; he has reportedly claimed that his personal collection is the fourth-best in the world of its type.

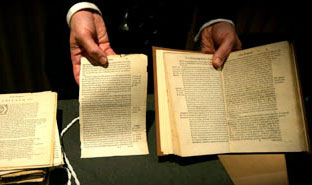

In May 2008, Hakimzadeh pleaded guilty to 10 counts of theft at the British Library (with 20 additional counts taken under consideration) and four at the Bodleian, but he is believed to have defaced or destroyed as many as 150 books at both institutions by using a scalpel to remove maps and illustrations in order to “improve” his own copies of the books. Ader sentenced Hakimzadeh to two years in prison for the crimes, saying, “As an author, you cannot have been unaware of the damage you were causing.… I have no doubt that you were stealing in order to enhance your library and your collection. Whether it was for money or for a rather vain wish to improve your collection, is perhaps no consolation to the losers.” Hakimzadeh was also ordered to pay £7,500 ($11,059) in costs, and Judge Ader ordered that he remain in prison for at least a full year before early release is considered.

Library officials were alerted to the thefts in June 2006, although Hakimzadeh is believed to have begun stealing items from the BL as early as 1998, and from the Bodleian beginning in 2003. A months-long internal audit using patron records at the BL revealed that Hakimzadeh was the only person who had examined all of the damaged books, and police detectives discovered approximately 30 stolen maps and illustrations at his Knightsbridge home. One particular world map, done by Hans Holbein the Younger, was identified by its gilt edges (present in the BL’s book, but not in Hakimzadeh’s copy into which the map had been inserted). It alone has been appraised at £30,000 ($44,235).

Most of the books damaged by Hakimzadeh related to European involvement with the Middle East and Central Asia, and dated from the 16th-18th centuries; several more modern books were also vandalized. The BL’s head of British and Early Printed Collections, Dr. Kristian Jensen, said that Hakimzadeh’s thorough understanding of the subject area made his thefts all the more disturbing: “He has a profound knowledge of the field. So, in a sense, from my point of view that makes it worse, because he actually knew the importance of what he was damaging.” Jensen described himself in several interviews with the British press as “extremely angry” over the thefts: “We extend a bond of trust to our readers, and Hakimzadeh has fundamentally broken that trust. … What he has damaged is our historical record of how this country has engaged with that part of the world.”

Jensen went on to describe Hakimzadeh as “somebody extremely rich who has damaged something which belongs to everybody, completely selfishly destroyed something for his own personal benefit which this nation has invested in over generations.” Hakimzadeh’s lawyer, William Boyce, claimed that his client suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder and was not stealing the items to sell them, although prosecutors told the court that Hakimzadeh sold at least one book containing a stolen illustration, profiting by more than £2,000. At the sentencing hearing, prosecutors also pointed out that these thefts were not Hakimzadeh’s first offense: In 1998 he paid the Royal Asiatic Society £75,000 ($110,587) in compensation after stealing nearly a 100 books from that institution’s collections.

Hakimzadeh’s lawyer claimed that his client suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder.

The 10 items Hakimzadeh admitted to stealing from the British Library are estimated to be worth £71,000 ($104,689), but the library estimated that total costs for repairs to the damaged volumes will be much higher, and the losses of the still-missing materials have been called “incalculable.” The library has filed a civil suit against Hakimzadeh for restitution and damages, which is proceeding. In an interview for this column, Jensen said that the British Library is “very pleased” with the criminal verdict in “this very complicated case,” and that they look forward to an eventual resolution of the civil suit.

The BL, which also suffered at least one theft by E. Forbes Smiley, has increased its security measures since Hakimzadeh’s crimes were discovered, adding additional security cameras (which Hakimzadeh was able to avoid) and augmenting the number of staff members on the floor in the rare books reading room. Other comparisons with the Smiley case are unavoidable: Smiley’s federal sentence, considered much too lenient by most observers, was three and a half years, plus $2.3 million in restitution payments, for the admitted thefts of 97 maps from six different libraries. As in that instance, Hakimzadeh’s prosecution speaks to the importance of good cataloging records and the permanent retention of patron use files in rare book rooms. Dr. Jensen also stressed that this case speaks to the need for libraries to quickly and completely acknowledge thefts from their holdings: “Be up front about it,” he said. “Put your head above the parapet so it can be dealt with.”

According to British media reports, Hakimzadeh slowly nodded his head as the judge pronounced his sentence; members of his family, watching from the gallery, shed tears. Sometimes bibliomania goes too far, and when it does, justice must be served.

Jeremy Dibbell, an assistant reference librarian at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston,

Jeremy Dibbell, an assistant reference librarian at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston,