Food Junk

The Wondrously Weird World of American Culinary Ephemera

By William Woys Weaver

The word ephemera is not new to collectors of printed materials, but its association with the term culinary is definitely a new twist. Perhaps it was inevitable that culinaria would gradually evolve into a distinct category, not only because it holds so much appeal for collectors, but because the study of food and the history of eating habits are quickly coming together as a specialized science in academe. Just as archeology needs artifacts for its interpretations of culture, so do food studies require more than cookbooks to understand the ever-changing role of food in human society. I’ve been considering the artifacts shown here for a book that will aim to set forth the “science” of culinary ephemera.

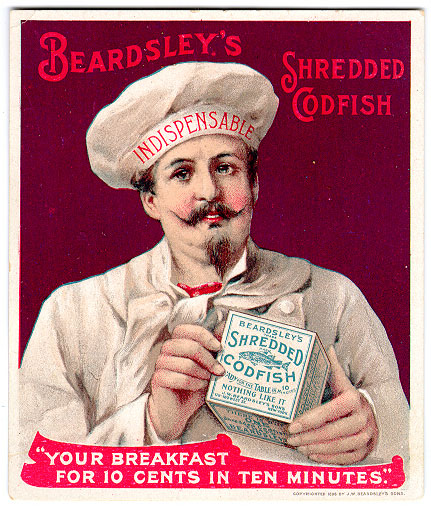

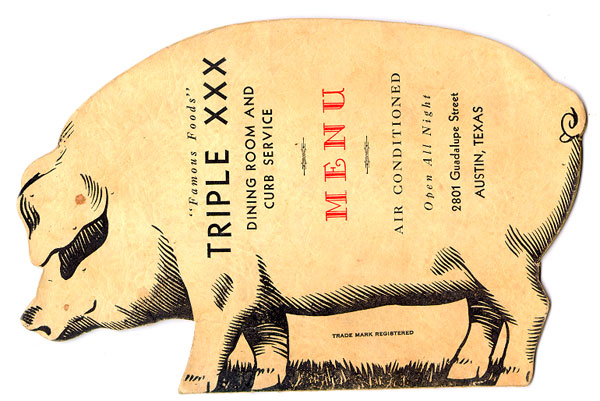

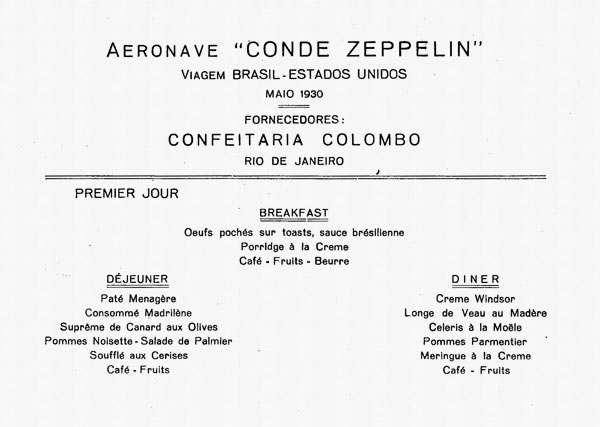

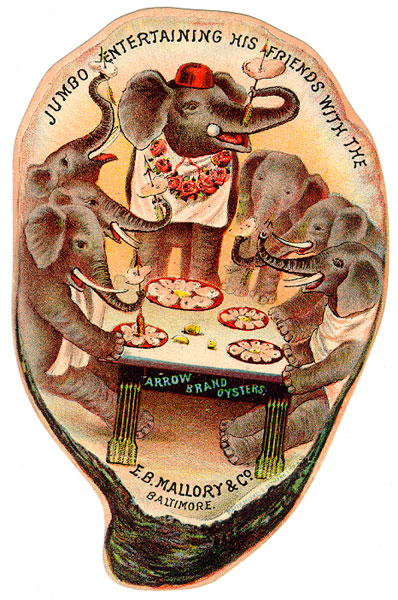

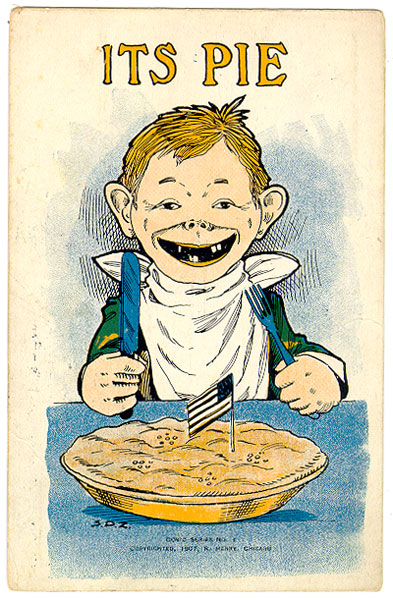

Collectors of culinary ephemera are already legion, although the market is highly fragmented into discrete groups. Some people collect menus. Others collect trade cards, pamphlet cookbooks, match covers, post cards, railroad ephemera, valentines, labels and stickers, wrappers and packaging, and even sheet music with food themes. When we consider just how pervasive food is in our daily lives—from the spatulas and salt shakers in the kitchen, to the chairs and tables where we eat, or the rows upon rows of packaged goods in most supermarkets—we can easily construct narratives about ourselves, our aspirations, our value judgments, even our foibles. While many people collect culinary ephemera for the nostalgia factor or eye appeal, I collect for the little stories these artifacts tell: a portrait of America constructed from its paper rubbish and hand-me-down mementos. Should you doubt the importance of culinary ephemera, just pull over to the side of the road sometime and take a look at how much our litter has to do with food.

I’ve been collecting culinary ephemera for a good 30 years, as a sideline to collecting culinary antiques, old cookbooks, and the heirloom seeds I wrote about in Heirloom Vegetable Gardening. I’ve always cultivated this holistic approach, because ephemera can provide critical documentation for objects, for important individuals in the history of food, and of course, for foods and dinners of the past. Though culinary ephemera remains relatively affordable, the age of 10-cent flea market bargains is behind us. Like rare old cookbooks, well-chosen representations of a specific genre have definite resale value and high appeal to research institutions looking to build up collections about food.

The most obvious area for collectors is menus. Many libraries, including the New York Public Library, have already assembled large and impressive collections. Some of the highest prices paid for culinary ephemera go for menus, although the mythology of what is desirable (as opposed to what is historically important) can be quite confusing. A menu autographed by Joe DiMaggio can fetch a huge sum at auction, but that price is not about the food and drinks at DiMaggio’s nightclub in San Francisco; it’s about an autograph, a baseball hero, and, of course, the association with Marilyn Monroe. In short, that menu is an icon for an era. An early menu from The Four Seasons in New York, or from Chez Panisse in Berkeley, would have far more historical value because of the culinary revolutions that emanated from those two restaurants. (But perhaps only readers of Patric Kuh’s The Last Days of Haute Cuisine would know that.)