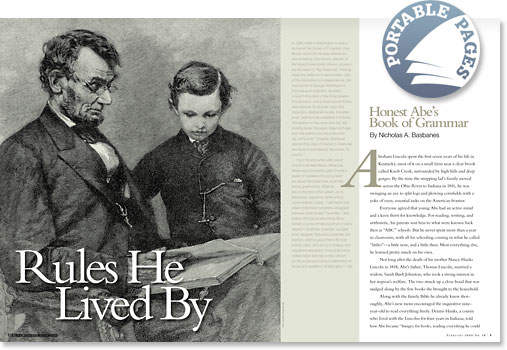

Rules He Lived By

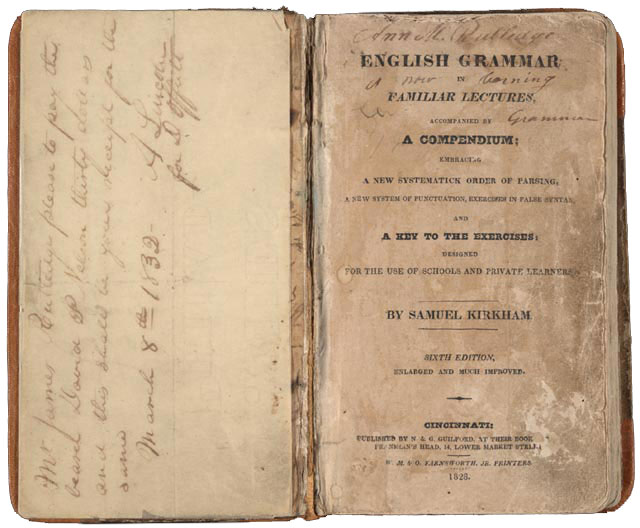

In 1996, while in Washington to give a lecture at the Library of Congress, Fine Books columnist Nicholas Basbanes was invited by Clark Evans, director of the library’s rare books division, to examine the nation’s “Top Treasures.” Among these are Jefferson’s hand-written copy of the Declaration of Independence; the manuscript of George Washington’s First Inaugural Address; Abraham Lincoln’s first draft of the Emancipation Proclamation; and a small volume Evans described as his favorite. Upon first inspection, Basbanes recalls, the latter book “seemed the unlikeliest of choices. The leather on the cover was dull, the binding loose, the paper faded with age, even the edition was not a first printing, but a sixth.” Gingerly, Basbanes opened this copy of Kirkham’s Grammar and found it inscribed by the owner, “A. Lincoln.”

From his encounter with one of Lincoln’s earliest literary influences, Basbanes conceived a plan to write a series of narratives for young readers about the books that most influenced great minds. What follows is the first in this series—or so Basbanes, waylaid by other writing commitments, hopes. “I still harbor the dream that these narratives will appear between hard covers,” he writes, “ illustrated with original artwork by Barry Moser, a consummate bookman in every respect—illustrator, engraver, typographer, designer, fine press publisher, bibliophile—and my good friend for over twenty years. Should such a happy consequence take place, it would be a true collaboration between writer and artist, the single goal being a celebration of books and readers in all their glory.”—Ed.

Abraham Lincoln spent the first seven years of his life in Kentucky, most of it on a small farm near a clear brook called Knob Creek, surrounded by high hills and deep gorges. By the time the strapping lad’s family moved across the Ohio River to Indiana in 1816, he was swinging an axe to split logs and plowing cornfields with a yoke of oxen, essential tasks on the American frontier.

Everyone agreed that young Abe had an active mind and a keen thirst for knowledge. For reading, writing, and arithmetic, his parents sent him to what were known back then as “ABC” schools. But he never spent more than a year in classrooms, with all his schooling coming in what he called “littles”—a little now, and a little then. Most everything else, he learned pretty much on his own.

Abe once joked that he probably had read every book he ‘could hear of for fifty miles around.’

Not long after the death of his mother Nancy Hanks Lincoln in 1818, Abe’s father, Thomas Lincoln, married a widow, Sarah Bush Johnston, who took a strong interest in her stepson’s welfare. The two struck up a close bond that was nudged along by the few books she brought to the household.

Along with the family Bible he already knew thoroughly, Abe’s new mom encouraged the inquisitive nine-year-old to read everything freely. Dennis Hanks, a cousin who lived with the Lincolns for four years in Indiana, told how Abe became “hungry for books, reading everything he could get his hands on.” When each day’s chores were done, he loved nothing more than to take a piece of warm cornbread off the stove, sit in a chair by the fireplace with his long legs stretched up “as high as his head,” and spend the rest of the night absorbed in some new volume he had just come across. Anything set down on paper stirred his curiosity and fired his imagination.

From Aesop’s Fables, Abe learned moral tales that he would use years later to make important points in his political addresses, public debates, and daily conversation. He would recall how Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe thrilled him with its riveting yarn of survival on a desert island. The uplifting story of another poor boy like himself who was eager to make his way in the world Ben Franklin’s Autobiography delighted him, and for pure pleasure and wanderlust he lost himself in the exotic Tales of the Arabian Nights. One of the most widely read books in early America, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, moved Abe so deeply with its fast-paced message of hope and salvation that he was unable to finish his supper one night, powerless even to fall asleep. And then there was the unending magic of poetry, with the plays of William Shakespeare and the verses of Robert Burns becoming special favorites that he would return to again and again, quoting favorite passages from time to time at apt moments, reciting phrases word for word.

Nicholas A. Basbanes recently received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to work on his book on paper, which is forthcoming from Knopf. His most recent book is Editions & Impressions, a collection of essays. His other works include the acclaimed A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.

Nicholas A. Basbanes recently received a National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to work on his book on paper, which is forthcoming from Knopf. His most recent book is Editions & Impressions, a collection of essays. His other works include the acclaimed A Gentle Madness, Every Book Its Reader, Patience & Fortitude, Among the Gently Mad, and A Splendor of Letters.