Heaven Sent

When Homeowners’ Insurance Came Straight from the Top

In these days of domestic disaster, of home foreclosures and lost jobs and frozen credit, what protection is available to the average American? For several centuries American homeowners had insurance in the form of a printed document called a Himmelsbrief—or Letter from Heaven. Carried on the person, especially in time of war, or framed and installed in the farmhouse, the letter was believed to furnish protection of many sorts. The document was universal among the Pennsylvania Dutch, as well as among the Dutch Diaspora in the South, the Midwest, and Canada.

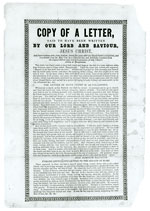

Like other broadsides, letters from heaven were sold at fairs and markets in the towns and peddled through the countryside. Dozens of versions, in German or English, were printed and sold during the 19th and 20th centuries, and even today variants may be found. The letters were typically framed and displayed in the house for protection, although a family might turn the text to the wall in the event of a visiting pastor, since many clergymen considered such documents superstitious. Pennsylvania Dutch soldiers in all our American wars carried them folded in their uniforms.

The stark appeal of a Himmelsbrief was its claim to have been written by God (or, more accurately, by Christ) and sent down from Heaven to various sites on earth. A heaven-sent letter served as blanket insurance coverage from fire, flood, and pestilence; making duplicate copies was not only acceptable but encouraged as a way to spread God’s blessings around. The letters included admonitions to practice Christian habits and virtues, to honor the Sabbath by refraining from work and by attending church; help the poor and unfortunate; avoid arrogance and fashion. Woe to any who rejected a Himmelsbrief, for he would be rejected by Christ at the Last Judgment.

The most common version of the Himmelsbrief was the so-called Magdeburg Letter with its made-up date of 1783. In truth, the earliest known printed examples date from German presses in Munich, ca. 1500, just a half-century after the invention of printing. Still earlier examples, of the so-called St. Michael’s Letter, originated either in France or England, from “St. Michael’s Mount” on the English Channel, a pilgrimage shrine that held great attraction during the Middle Ages. As there are two such shrines with this same name—Mont St. Michel in Normandy and St. Michael’s Mount across the English channel in Cornwall—we shall let the medievalists fight it out among themselves to determine the letter’s ultimate origin.

The universal popularity of the Himmelsbrief among the Pennsylvania Dutch derived its having all the accoutrements of a worldview held only by ultra-conservative Christians today: Heaven, Hell, Salvation and Perdition; the Heavenly Host of Angels and Archangels; and sins, curses, and blessings. The letters set forth a kind of truncated Ten Commandments, with Protestant notes of opposition to outré dress, fashions, cosmetics, and fancy hairdos. (Protestant, yes, although most of these Puritan ideas can be found in the Middle Ages as well as in later Pietism and Evangelicalism. )

Secondly, the Himmelsbrief represented to the folk mind an example of post-biblical revelation, a new and novel message from God postdating the last word of the Bible. Letters from heaven were kin to the New Testament Apocrypha, especially the Gospel of Nicodemus, which the Pennsylvania Dutch likewise kept in print for two centuries.

A heaven-sent letter served as blanket insurance coverage from fire, flood, and pestilence.

Thirdly, the letter is both a warning and an encouragement to keep on the narrow way that leads to salvation and not the “broad way” that leads to destruction. Fortunately, and most important of all, the letter is itself a paper amulet, an apotropaic device allegedly with the power to ward off various dangers that threaten human life and happiness.

The Himmelsbrief should be considered an example of folk religion rather than official Protestantism, yet many churchgoers embraced Himmelsbrief. One Sunday School teacher in Berks County, Pennsylvania, printed up copies inscribed with his name and distributed them as gifts to his Sunday school pupils.

Related documents in the Pennsylvania Dutch culture–Himmelsbrief of sorts–include the “Fire Letters” to ward off destruction of farm buildings by fire, an ever-present danger in the past from lightening strikes and even from spontaneous combustion in haymows. The prime example was the “CMB-Letter,” which consisted of prayers to the Three Wise Men, Caspar, Melchior, and Bathasar. (Catholic tradition conveniently discovered the names not mentioned in the Bible.) The cult of the Three Wise Men, or the Three Holy Kings as they are alternately called, centers in Cologne, and the document came to America with the Rhineland immigrants to Pennsylvania. The example shown here was published at Kutztown, Pennsylvania, in the 1870s.

In Europe, heavenly letters were not limited to the German-language orbit. Scandinavia had them; England had them, too: See the Iconium Letter reproduced in this article. And there is even a curious Italian version that occasionally surfaces in Italian-American families. Entitled La Sacra Lettera di Gesu Cristo, it conveys the same encouragements to virtue and warnings against sin as our Pennsylvania Dutch examples.

One additional related broadside deserves mention here: the Haus-Segen or House-Blessing. This was usually a rhymed prayer to bless the house and its household of family members. It was often framed and put on the wall of the farmhouse. Because of its prayers, it was closer to the standards of official religion than was the folk-religious Himmelsbrief.

Today, examples of Himmelsbrief occasionally turn up, either framed or loose, at antique shows, flea markets, and folk festivals in the Dutch country of Eastern and Central Pennsylvania. Prices range from $400–$500 for the earliest 19th-century examples, to an average of $75 to $125 for later printings. My advice to the reader and would-be collector, in times like these, is to scour the back roads of Pennsylvania in search of a broadside peddler, and to bring home a letter from heaven to protect yourself and your property.

Heaven knows, the bankers won’t do it.

Don Yoder, a professor emeritus of folklore studies at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the author of The Pennsylvania German Broadside: A History and Guide (2005) and more than a dozen other books. He donated his collection of Pennsylvania Dutch broadsides to the Library Company of Philadelphia. He is working on a book about the Pennsylvania Dutch form of folk medicine known as “powwowing,” which makes use of magical charms to heal the ailments of humans and animals.