Ibsen, Hamsun, and a Tiny Smoked Fish

On a Self-Guided Literary Tour of Norway, Wonders Abound By Erica Olsen

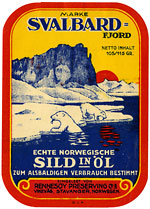

Polar bears on ice floes. Speed skaters and Vikings. Polar explorers swathed in Arctic gear. In the early years of the 20th century the print shops of Stavanger, Norway, created these and other throwaway masterpieces of color lithography by the millions, all to market a tiny smoked fish.

A fish just like the ones hanging in a silver row in front of me, neatly threaded on skewers. It was the day they fired up the smoker at Stavanger’s Hermetikkmuseum, or Canning Museum, and the apron-clad men knew a sardine-eating novice when they saw one. “Twist off the head,” they told me.

As North Sea oil replaced sardines in Stavanger’s economy, the industrial history of Norway’s fourth largest city was at risk. “It was essentially the former workers who got together” and saved the equipment that is now in the Norsk Grafisk Museum, or Printing Museum, said Crocker. “They’re very strongly unionized, printing workers in Norway. And so they put the word round: Are there any volunteers who would like to do this and keep the old skills going?”

The gem of the Printing Museum collection may be its dozens of lithographic stones with original label artwork, iconic images like the sardine-loving polar bear. Some of the stones were saved by chance. “Somebody was using them upside down as a garden path here in Stavanger,” Piers Crocker explained—and there they remained until someone recognized the telltale rounded corners.

The Printing Museum is open for group tours by arrangement. According to Gunnar Nerheim, director of Stavanger Museums (which administers both the Canning and Printing Museums), plans are pending for the Printing Museum to move to a new location closer to the city center.

The Poet’s Town

While Stavanger’s printing history seems serendipitous, Grimstad, on Norway’s south coast, has capitalized on its literary heritage, marketing itself as the dikternes by (poets’ town).

Henrik Ibsen arrived in Grimstad as a pharmacist’s apprentice in 1844 and began his writing career there. His relationship with the town during his six-year stay was fraught; he fathered an illegitimate child, and his play The Pillars of Society, 1877, criticized Grimstad’s provincial society. But association with literary celebrity meant opportunity for Grimstad. In 1916, just ten years after the playwright’s death, the town opened its Ibsen Museum in the building where the young Ibsen had lived and worked. (Other Ibsen museums would follow in Oslo and Skien, his birthplace.)

Today Grimstad is a town of 20,000 and a popular summer resort. But on a winter visit, with snowy streets muffled in fog, it was easy to imagine the town of Ibsen’s time. The museum is closed during the off season except by arrangement; I was fortunate to have Gunnar Edvard N. Gundersen of the museum staff as my guide through the pharmacy and Ibsen’s room (both with original furnishings). “Ibsen was born in Skien, but the writer Ibsen was born in this room,” Gundersen said. With exhibits renovated in 2006, the museum focuses on the young man writing in the sparsely furnished room behind the pharmacy, who could not know that gilded editions awaited him. This was the Ibsen who lived in Grimstad—“not that boring guy with the beard,” Gundersen laughed. The museum’s interpretation combines history with a fresh, contemporary sensibility.

At the museum, you can still find the bearded Ibsen presiding over his first editions, including his scarce first play, Catilina, 1850, published under the pen name Brynjolf Bjarme. Also housed at the museum is the library of the former Grimstad læseselskab, or reading society—a 19th-century precursor of the public library. It’s believed that Ibsen had access to this collection of 300–400 books. The well-used volumes, many bearing old catalog numbers on their spines, come across as a bridge between small-town Grimstad and the world of authorship the young Ibsen aspired to.