All the Presidents’ Desk

How the Quest for the Northwest Passage Ended in the Oval Office

By Derek Hayes

When Barack Obama took office, and the press revisited all the trappings of White House power, not least of these was a desk in the Oval Office. Such is the remarkable history of the Resolute desk, that maps, rather than provenance, may best tell its story.

The desk is made from timbers from the British ship HMS Resolute. It was once common for wood from British naval ships to be made into all sorts of mementos after being decommissioned and broken up. Early recycling, I suppose! I remember my parents had an ashtray on their mantelpiece when I was growing up; a little plaque named the ship it came from—HMS something. The advisability of having an ashtray made of wood is questionable, but I guess it wasn’t really meant to be used.

Resolute was abandoned in the Arctic in 1854, after becoming entrapped in ice, but over a period of 16 months it mysteriously sailed itself eastward and then southward, going with the currents. When in September 1855 it appeared in Davis Strait, between Greenland and North America, an American whaling ship discovered it and sailed it back to New England as a salvage prize. The American government then purchased the ship, had it refitted, and sailed it back to Britain, where it was presented to Queen Victoria as a token of peace and esteem.

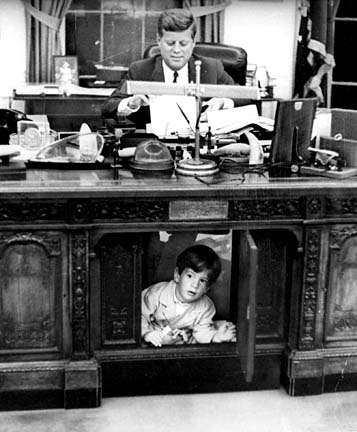

The ship was finally decommissioned and broken up in 1878, whereupon Queen Victoria decided to return the Americans’ compliment. She presented a desk made from its timbers to President Rutherford B. Hayes, who placed it in the Oval Office. There it has mostly remained (a few presidents moved it elsewhere in the White House). The desk is much as it was, with one exception: President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered a front panel made to hide his wheelchair.

Since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe in 1815, the British had been probing the North American Arctic in search of the fabled Northwest Passage, a supposed easy route between the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans. Although they met with considerable success, showing that a passage—albeit, mainly frozen—did exist, no one had managed to actually pass through. In 1845 the famous Arctic explorer John Franklin set off with two ships on his ill-fated expedition to sail through the passage, from east to west, only to become trapped by the unforgiving ice in September 1846. The crews attempted to trek over ice and land south to safety; all died in the attempt. More than 50 expeditions followed, all searching for Franklin even long after he could possibly have been alive. These trips explored and mapped the Arctic far more extensively than Franklin ever could have done himself. And in the process, the Northwest Passage was finally transited.

Success, however, essentially required a joint effort. In 1850 a two-pronged expedition was sent out: Four naval ships, among them Resolute, joined two other privately-financed vessels to search from the east (and two other privately financed American ships joined in, though not with the rest), while two ships were to sail through Bering Strait and search from the west. These latter two became separated; one, HMS Enterprise, under Captain Richard Collinson, spent longest in the Arctic because it was repeatedly trapped in ice, and did not return to Britain until 1855. The other, HMS Investigator, under Captain Robert M’Clure, was trapped in the ice and never returned, but its captain and crew did, after being rescued by crews from Resolute.