Postcards from Havana

A Show of Cuban Artist Books Is No Message in a Bottle

By Richard Goodman

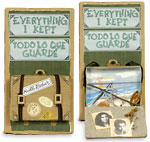

The venerable Grolier Club, in the heart of midtown New York, is about 60 blocks south of the former Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where Fidel Castro and his entourage famously, and boisterously, stayed in the summer of 1960. I mention this fact because anything artistic coming out of Cuba is going to be considered in a political context, even a relatively narrow—though gratifying—show like this. The exhibition of Cuban artist books now at the Grolier Club leaves nothing to chance in that respect: An accompanying one-page handout states that the show’s opening “will coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Cuban Revolution.” The handout also says that the artists represented “have survived cultural politics, difficult living conditions, and resource shortages….” Strolling through the small exhibition room of the Grolier, regarding these books ingeniously cobbled together with verve, panache and wit, one wonders if these artists ever just want to be left alone, want not to have to be something other than just creative artists.

But while this group of more than 120 books, prints and assemblages may be rewarding to view on its own merits, we expect this art to have opinions, like any person who has just come to the U.S. from Cuba. Rightly or wrongly we expect there to be some sort of political message. Of course, we’re quite satisfied if this is a clever message, something hidden or transmitted through symbols, but we still look for the cry for help, for the visual voice of a Cuban Solzhenitsyn.

Exhibit curator Linda Howe, an associate professor of Romance Languages at Wake Forest University, says not to look so hard. “The show does not focus on politics,” she said. “Rather, the focus is on the art of bookmaking and the ingenious creativity of the artists in spite of difficult economic circumstances and the complexities artists and everyday citizens encounter in a country like Cuba. As you may know, Cuban artists have a long and complex history with cultural officials and the Cuban government. This also goes for all participants in the Cuban cultural milieu.”

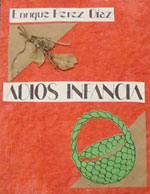

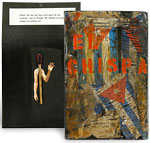

Howe is correct in saying that most of the art doesn’t convey a “message”—at least not blatantly or aggressively. The exhibit features 13 contemporary Cuban painters, sculptors, photographers and printmakers, among them Sandra Ramos, Sandra Ceballos, Ibrahim Miranda, Carlos Estévez, Rene Peña, Rocío García and Antonio Eligio Fernández—not familiar names, nor would they be, which is one of the points of the exhibit. The books and prints are often whimsical, almost always resourceful and inventive, and, in a few cases, beautiful. Many were published by Ediciones Vigía, a homemade publishing house that does not pay its authors but creates as many as 200 copies by hand for the authors instead. In a brief but satisfying video that accompanies the exhibit you see some of the Vigía volunteers at a table assembling books, cutting and stitching carefully, as if they were creating a fine dress. In fact, one of the more memorable works actually is a dress, by Carlos Estévez, with words nicely written across its airy, muslin fabric.