Made in Japan

Perry’s Expedition Forged Nearly a Century of Peaceful and Lucrative Trade

By Derek Hayes

The United States acquired a west coast in 1848, after the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican War. Then gold was discovered, and so in 1850 California was quickly made a state. California not only belonged to the United States, it was valuable to boot.

It was not long before the United States began to look westward across the vast Pacific in search of trade. One intransigent nation was not interested in trade with the U.S., or with anyone, for that matter. The emperor of Japan and his government feared that foreign influences would dilute their power and corrupt their people. There was even a Japanese law that any foreign ship that came within range should be fired upon. Clearly this would be a problem for any American ship in distress.

There was another reason for wanting to open up Japan to American ships. The use of steam powered ships for the U.S. Navy was just beginning, but such vessels needed a lot of coal, and, just like the British Empire at this time, the United States wanted to establish coaling stations around the world. And Japan had lots of coal reserves.

One of the top American naval officers, Matthew Calbraith Perry, was recruited to lead an flotilla to Japan to negotiate the opening of trade, or, failing that, to force the Japanese to trade with the United States—and supply the precious coal. Two of the four ships in his little fleet, the USS Mississippi and the USS Susquehanna, were steamships. The idea, based on the recommendation of Captain James Glynn, commander of a previous expedition which had briefly negotiated with the Japanese at Nagasaki in 1849, was to create an overwhelming display of force that would “shock and awe” the Japanese—a policy not unknown to the modern military strategist—so that the Japanese would think it a better idea to negotiate than to resist. So little was known of Japan at this time that the American government purchased for Perry some inadequate maps of the Japanese coast, from the Dutch, for the massive, almost unbelievable sum of $30,000.

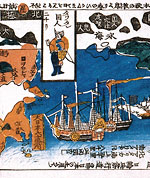

Perry’s ships—quickly dubbed the “black ships” by the Japanese because of the black smoke they belched—paraded into Tokyo Bay in July 1853, defying all attempts to board them. Perry sought out a Japanese official who could speak Dutch, the language of the trading community at Nagasaki—the one place Japan allowed foreigners to stay, albeit tightly confined to a small area. While waiting for the emperor to respond to a request to negotiate, Perry’s men engaged themselves in mapping the bay and collecting scientific information, all the while protected by ships’ guns. Perry carried with him a letter from U.S. President Millard Fillmore, which was finally presented to the provincial governor, Toda. That done, the Americans left, saying they would return the following spring for the emperor’s reply.

The following February Perry was back, this time anchoring at Kanagawa, Yokohama, at the entrance to Toyko Bay. He went ashore in a display of splendor, but also armed to the teeth—even the band was armed with pistols and swords. The emperor gave his answer: Most of the U.S. demands would be agreed to, but not all, and it took more negotiation, and more military displays, to get the Japanese to finally agree to all the American demands.

The result was the Treaty of Kanagawa, signed on March 31, 1854. It promised a “perfect, permanent, and universal peace” and “sincere cordial amity” between the two countries. The ports of Shimoda and Hakodate were granted by the Japanese as “ports for the reception of American ships. And, importantly, it was agreed that if any American ships were shipwrecked, the Japanese would assist them and not imprison American sailors.

You would think that such a treaty, imposed by force, would hardly be likely to last. Yet it did. Japan was opened to American trade—and once trade began, its benefits became so obvious that it was continued.

Although Perry’s expedition, correctly the United States’ Japan Expedition, was not primarily scientific in nature, he and his officers collected so much new material that Perry published the scientific results of the voyage in three large volumes in 1856-58. The books contained not only practical matters such as sailing instructions and the location of coal deposits, but also many maps and charts, illustrations and many details about hitherto unknown (to Americans) fish and other marine life, and an entire volume of “observations of the zodiacal light.”

Perry’s original charts are principally now in the U.S. National Archives, but many were engraved and printed and made available from his book, sometimes separate, sometimes not. And there are many beautiful and artistic paintings, such as that of the fish shown here.

Perry went ashore in a display of splendor, but also armed to the teeth.

Soon after Perry left for Japan, another expedition was assembled to follow in his footsteps and test the treaty that Perry was then expected to negotiate with Japan. This expedition, however, was not limited to Japan but had as its mandate most of the North Pacific Ocean, officially a “reconnaissance and survey for naval and commercial purposes, and especially for whaling. American whaling in the North Pacific was gaining in importance at this time, as whale oil was found useful for lighting. Scores of whalers sailed from New England ports round the Horn to the Pacific to engage in the lucrative trade. But many of the uncharted rocks and islands along the coasts proved to be the end of many a ship. The U.S. North Pacific Exploring Expedition, as it was called, was to chart all these navigational hazards as well as collect scientific information. Only one of the five ships was a steamship, as steamships needed a reliable and plentiful supply of coal. The expedition was led by Cadwalader Ringgold, latterly a surveyor of San Francisco Bay. After Ringgold became ill, command devolved onto Lieutenant John Rodgers. His ship, the USS Vincennes, was by this time well-traveled, having been the flagship of Charles Wilkes’s U.S. Exploring Expedition in 1838-42.

The expedition left the United States in mid-1853 and the two-year voyage visited Japan once more and was allowed access to ports, although sometimes a bit reluctantly. The important coal deposits were sought out around the Pacific, and the Vincennes even pushed north through Bering Strait and into the Russian Arctic near Wrangell Island, searching for other islands supposed to be in the region, but gathering information useful to American whalers on the way.

A vast amount of marine and botanical specimens were collected, most of which are now in the Smithsonian Institution. Again, the expedition produced a book, three large volumes, but plans to publish the book were scrapped when the Civil War intervened. Nonetheless, as with Perry’s expedition, most of the original maps were deposited in the National Archives, and they can be seen there today.

Derek Hayes is the author of a new book titled the Historical Atlas of the American West, which will be published by the University of California Press this fall.

Derek Hayes is the author of a new book titled the Historical Atlas of the American West, which will be published by the University of California Press this fall.